Perceiving

Waiting for a signal at a busy city cross-walk, a cluster of pedestrians gather. Each is experiencing personal and private streaming of perceptions, sensations, and thoughts in their minds. My mind: “I’m feeling chilly…that’s a cool dog over there…wonder if it’ll rain…I’m running a bit late…”.

We are all living in our own mind bubbles yet sharing some perceptions and intentions: waiting to respond to the crossing signal, being aware of the passing cars, and sensing approximately the same time and locality. As a dog fancier, I may see a dog passing across the street, likely not recognized by the others. We all experience the individual and private as well as the shared.

Neuroscience research using brain imaging techniques that tracks neural activity is making remarkable headway in understanding perception. A minute element in the environment is excised, received, modulated, and transmitted from the external world as stimuli by the sensory organs. This raw sensory input is distilled and transformed into neural activity that progresses along multiple pathways of the cerebral hierarchy.

In this progression neurons are communicating through complex neural networks and the various sensory inputs are fully integrated and unified. The neural activity is then transformed in the higher cortical regions into relevant abstractions through the use of language. The result: experience of ‘waiting for a signal at a busy city cross-walk.’

These seemingly instantaneous, streaming, cascading perceptions are embellished with familiar interpretations and are often associated with sensations and emotions. We experience and verbally report to ourselves or others—but it’s after the occurrence. And most amazingly, this entire mental presentation of the mind—including the implied behavior, street crossing when signaled—occur beneath the level of awareness.

Worthy of exploration

The science of the mind/brain tells us important information about the mind/brain/body that impacts every area of our lives—including finances. For instance:

1.) We each experience our world differently based on who we are.

Perceiving, thinking, planning, sensing—while mutually shared and agreed upon by others—is largely influenced by the state of mind, our life-long experiences, education, culture, language, age, developmental level, and heredity. As Anaïs Nin, an essayist, said: “We don’t see things as they are; we see them as we are.”

2.) We’re not aware of the activity beneath waking consciousness.

Mental activity presented in the mind—perceptions, thoughts, sensations, emotions that evolve into decisions, plans, opinions, and behavior all come about beneath the level of conscious awareness.“The brain knows before you do,” a chapter in Michael S. Gazzaniga’s book, The Mind’s Past, describes how systems built in the brain do their work automatically, largely outside our conscious awareness, and finish their work a half a second before we know it.

3.)The mind/brain infers and interprets from minimal input to construct and present a ‘whole presentation’. The magnificence of even a simple moment of the mind/brain activity requires incredible assimilation, integration, interpretation, and sheer intelligence. Yet, the brain pulls it off—with a great deal of inference involved. Our conviction of the ‘obvious’ may not always be as obvious as we rely upon. Because, the mind fills in more than it takes in.

This picture might seem to contradict our reality of solid objects and people moving about. Everything is very ‘real’, ‘concrete’, and so ‘obvious’. How can our experience of reality be so flimsy, personally-molded, lacking certainty and solidity, arising from who knows what and from where? How can this be?

This is so because the mind/brain is subject to biases of perception, judgment, and memory. Nevertheless, by using its incredible power, the mind/brain can cajole itself to expand, broaden its perspective, understand itself better, ‘let more light in’ and, most importantly, allow that “I may not know everything I think I know.”

In this blog posting and the next post we’ll explore ways the mind can utilize its inherent power to realize more expansive and insightful perspectives:

Taking perspectives: Four-quadrant approach

In this blog, we’ll examine the four-quadrant approach to perspectives. In the next blog posting, we’ll deepen our exploration of the mind’s nature and pitfalls from a cognitive behavioral perspective.

Minds have viewpoints, take perspectives. An indispensable approach to understanding our inherent ability of taking perspectives is the four-quadrant approach outlined in Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory called AQAL. His work is readily available on the web; the first book of his that I read over two decades ago is A Theory of Everything.

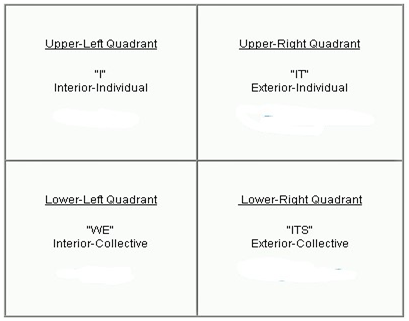

In his research, Wilbur found that the whole of human knowledge and experience can be roughly categorized into a four-quadrant grid. Along the vertical axis is singular and plural; on the horizonal axis is subjective and objective or interior and exterior. See the diagram below:

These quadrants can be easily grasped with the familiar pronouns: I, we, it, he, she, and they. We can see our normal way of thinking and communicating freely moves among the four-quadrants. Let’s take a closer look at the normal pattern of the mind’s perspectives:

Four Quadrant Financial Planning

Addressing any complex problem—be it climate change, high rates of suicide, gun violence, food and water security—necessitates four-quadrant analysis, as does personal finance. Personal finance includes not only the‘numbers’ like net worth but also a storage bin full of individual perspectives. And our finances invariably expand to include others, partners and family members—each with their own attitudes and preferences. Complexity abounds in even the simplest act of investing in a mutual fund to the larger context of financial institutions and the industry’s myriad products.

Each individual would benefit enormously from examining their personal relationship with money using this four-quadrant approach. Below is how we use this with clients to pull it all together.

First quadrant – ‘I’

We begin in the first quadrant with the client. We explore together how they think and feel about their finances including desires, concerns, and opinions. This is an integral part of engaging with our personal finances.

To open the discussion, we review a survey that we’ve asked them to complete. This survey captures their level of satisfaction across an array of financial matters like work and income; level of spending and saving; indebtedness; retirement readiness; and survivorship and estate planning. The key is engaging in an open discussion without the slightest judgment.

In turn, with the client, we uncover values, goals, challenges, levels of understanding, and commitment to addressing finances. Open non-judgmental discussions about personal financial matters are rare in our culture. Yet such discussions are vital to face financial reality and open the way to integrating finances in our minds and lives.

Second quadrant – ‘We’

The ‘we’ quadrant explores financial relationships in the client’s life. A couple sharing finances is two individuals so we ask each to complete the survey independently. It’s usually a light-hearted interaction as we compare and discuss discrepancies. It’s not uncommon that a couple talk more meaningfully about their finances and beliefs in our meetings than at any other time in their relationship.

One of the common discrepancies is the level of risk taken in investments; this is relatively easy to settle with compromise. The more challenging difference is on spending; an example, the woman who clips coupons finds it irritating that her husband will spontaneously buy a $2,000 ‘toy.’

In addition to spouses and partners, other family members are also addressed in second quadrant planning needs, including supporting children’s education. Clarity is important not only for the parent’s finances but also for the child to explore their future and college in the context of their financial support.

The financial status of the clients’ parents can enter second-quadrant planning. Obligation to care for one’s parents or in-laws may enter into financial decisions. Or, grandparents wish to gift to their grandchildren’s education.

Planning may help reduce stress for those in their 50’s. Many are faced with allocating resources among saving for retirement, covering children’s college expenses, and helping aging parents within adequate finances.

Third quadrant – ‘It’ or single -objective.

The third quadrant is unambiguous. It involves the specifics of the individual(s) quantitative personal finance information. This is the ‘black and white’ world of numbers: spending, income, savings rate, net worth, debt, cash flow/income. Data gathering and analysis includes diversified assets of real estate, stock options, deferred compensation, and business equity ownership—each with tax considerations. It’s objective and data-driven. And, the more ‘paper trail’-supported data, the better since memory can be somewhat unreliable, particularly on spending.

Fourth Quadrant – ‘They’

This quadrant represents the complexity and interrelatedness of the economy and markets, governments, financial institutions, and more. The interrelatedness is truly mind-boggling.

What’s important for the individual investor? Emerging from this complexity is the array of investment vehicles available to the client: What vehicles are most suited toa particular goal? Is the level of risk appropriate to both the time horizon and client’s comfort level? Have taxes been adequately considered? How does the client feel about this investment?

Creating the plan

Conclusions

The information provided here is for general information only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice.

The LPL Financial registered representative associated with this page may only discuss and /or transact securities business with residents in the following states: WA, CA, CO, WY, FL, NY, MD, OH.

Securities and Advisory Services Offered Through LPL Financial A Registered Investment Adviser Member FINRA/SIPC.

Legal services offered through Law Office of Cynthia J. Cannon. Legal services are not affiliated with LPL Financial.

Copyright 2024 Cannon Wealth Management, LLC, All Rights Reserved.

Designed & Developed by Altastreet.